The Inside Story Of Vince Russo's Jump From WWE To WCW

Vince Russo leaving WWE For WCW explained

Oct 30, 2025

Vince Russo is remembered as one of the most polarising figures in the history of professional wrestling. More than a quarter of a century after his name first became familiar to wrestling fans, Russo is more synonymous with pro wrestling negatives than positives, as his work across multiple promotions has left him with an extremely mixed legacy, to put it mildly.

Regardless, the complete story of the then-WWF's Attitude Era cannot be told without Vince Russo as he was firmly entrenched in creative at the time during WWE’s turnaround. Russo’s penchant for shocks was packed deeply into Attitude's soul, so much so that when Russo decided to jump ship to the WWF's festering rival, WCW, in 1999, it felt like one of those jarring plot twists that Russo enjoyed booking - except this was no angle.

Pro wrestling's connoisseur of chaos broke into the business from the peripheral edge. A 30-year-old Russo owned a video store in Long Island, New York in 1991 which sponsored local radio show Pro Wrestling Spotlight hosted by John Arezzi. After appearing as a guest on the show, Russo convinced Arezzi to move the radio show to Manhattan while Russo, a journalism graduate at Indiana State University, proposed publishing an insider newsletter to complement the programme.

The timing was perfect for Russo's brand of antagonistic brashness. At that point, the WWF was in the midst of several scandals, both sex and drug-related. By the spring of 1992, Russo was using his forum to excoriate both Federation management and their PR department for their response to the blitz of public scrutiny.

Shortly after, Russo was summoned to meet with Vince McMahon himself. It was after that meeting that Russo's stance toward the WWF completely changed and he broke away from Arezzi to begin Vicious Vincent's World of Wrestling, a pro-WWF programme that was permitted access to McMahon's top stars.

For both sides, it was a calculated business move. In Russo's case, the transition into wrestling came as his video store business was waning. Even with the WWF-endorsed radio show, Russo still found himself in financial peril and after a year on the air, Russo dissolved his programme to begin writing for WWF Magazine on a freelance basis, after personally penning a letter to Linda McMahon.

Quickly, Russo rose through the publication's ranks, becoming editor by early 1994. He also penned shouty, in-your-face musings under the pseudonym Vic Venom, beginning in the mid-1990s. It was with Russo at the magazine's helm that any semblance of straightforward dryness dissipated. Sentences in all caps, hot take-laden rants, and all manner of angsty edginess became WWF Magazine's norm on Russo's watch.

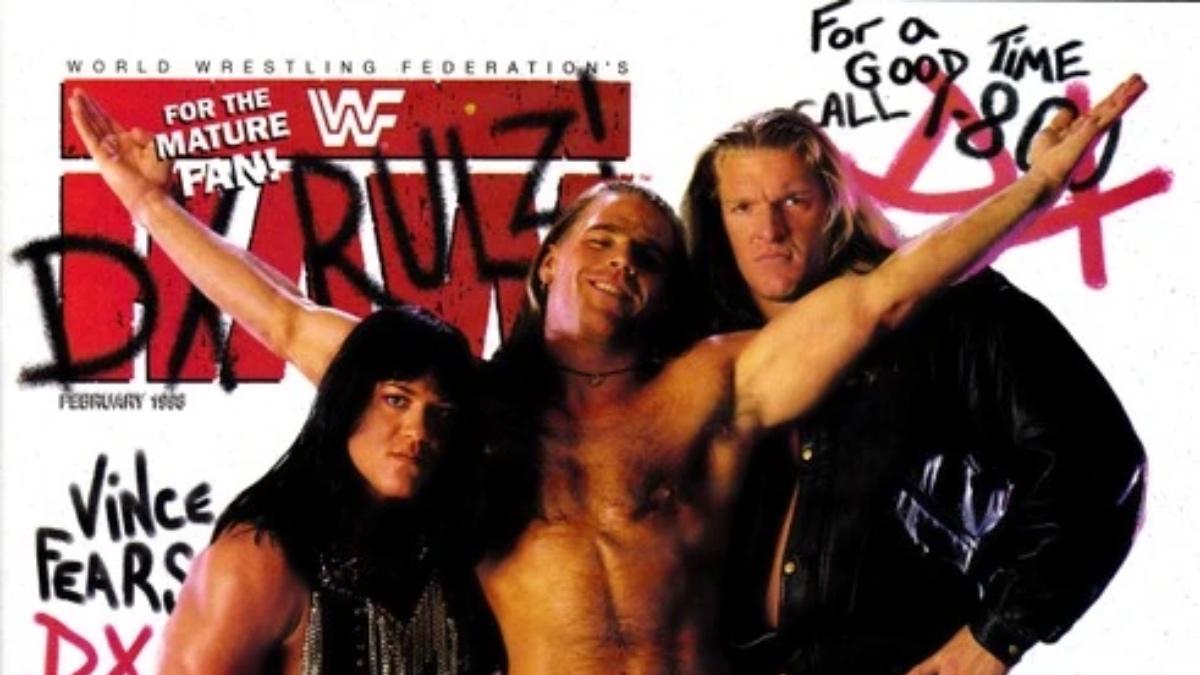

While primary WWF Magazine mostly remained kid-oriented, Russo was on hand for the 1996 inception of Raw Magazine, a secondary periodical with a slightly-more mature look at the WWF, including a fewer punches-pulled glimpse at the real life behind the melodrama.

It was Raw Magazine that helped move Russo further up the ranks of the industry and by the end of 1996, Russo - who sometimes made occasional weekend TV appearances as Venom - was sitting in on WWF creative meetings. Early the following year, a taped Raw broadcast from Germany was slaughtered by Nitro in the Nielsen ratings. A frustrated McMahon summoned his inner circle - Russo included - for what initially seemed like a post-mortem to discuss what went wrong.

At that meeting, McMahon reportedly threw down a copy of the edgier, less-cartoony Raw Magazine in front of the WWF's top officials and said, "This is what our show needs to be."

With that hasty endorsement, Russo soon became the WWF's head writer.

The WWF product had already been leaning toward a more shades of grey approach, but with Russo wielding creative sway, the lines grew blurrier. "Stone Cold" Steve Austin was a good guy, but a virulently anti-heroic one at that, while Bret Hart was a bad guy, but one that made salient points in the realm of geopolitics. Fewer wrestlers were painted with broad strokes in the more Russo-fied WWF, as nobody trusted anybody, and everybody had fighting words to impart.

For the most part, nobody followed the rules any more, just as Russo's creative - for better or worse - ignored the rules of conventional wrestling booking. Wrestlers switched from babyface to heel and vice versa with noticeable frequency. Titles also began changing hands just as often, as the days of era-defining reigns went out the window.

The product also sometimes employed the still-novel concept of "worked shoots", where wrestlers would drop character to acknowledge behind-the-scenes matters. There was also a stable war among factions representing different racial groups, while sex and violence reached unprecedented heights in the WWF, and cursing became a regular occurrence across WWF TV.

Chaos was what WWF became synonymous with, often being described as "Crash TV" as Russo’s philosophy was that there always needed to be something on screen to keep viewers from changing the channel, for fear of missing something important.

While Russo's influence was evident, however, he didn't have the final say on the product. Vince McMahon remained the head of creative, he was just a firm believer that "Crash TV" was the company’s best way to fight the ongoing Monday Night Wars with World Championship Wrestling.

WCW remained on top as 1997 came to an end, but the momentum had swung in WWF’s favour by the middle of 1998 primarily though the ongoing feud between Steve Austin and Mr. McMahon, the heel persona that McMahon created in the aftermath of the Montreal Screwjob. When Austin famously challenged McMahon to a match on April 13, Raw beat Nitro in the ratings for the first time in 22 months.

That June, Russo gained a new ally in the creative department when the WWF hired Ed Ferrara, a writer for the USA Network series Weird Science. Ferrara was no stranger to wrestling, having supplemented his script work by moonlighting as grappler Bruce Beaudine on the California indie circuit.

After Ferrara's hiring, the WWF product began straying even further from industrial conventions. TV matches became shorter, and they were almost always laden with interference. Top stars appeared in numerous backstage segments throughout the night, as opposed to being used sparingly to avoid overexposure. An emphasis was also put on dialogue, rather than the cliched stand-up promos of another era. TV segments ensured there was always something happening to advance a plot, whether major or minor, sensible or questionable.

By Russo's own admission, he and Ferrara would book angles for the wrestlers with Jerry Springer on TV in the background. By the end of their meetings, they would have an angle for just about everyone of significance, and they would take their outline to Vince McMahon, who would mould the program with his own input. From there, the final drafts of weekly Raws came together.

The audience caught on big time to this version of the WWF, during what was a lucrative boom period for the business. Raw began setting new ratings records for episodic American wrestling, while widening the gap over Nitro.

By 1999, Austin, The Rock, The Undertaker, D-Generation X, Sable, Mick Foley, and even Vince McMahon himself were all major television stars, performing for millions of viewers every week on a successful wrestling show that redefined what televised wrestling could, and perhaps even should, look like.

Though reined in with some semblance of structure and oversight, Russo was a large part of the WWF's turnaround and the late-1990s configuration of mainstream pro wrestling. Despite this, the man himself wasn’t entirely happy as burnout became a major issue.

Russo has admitted by the middle of 1999 that Monday Night Raw consumed his almost every waking thought, and that he was forced to prioritise McMahon over his wife and kids at home, missing out on important life events with his loved ones due to work commitments.

His workload was due to become even heavier too as the UPN Network premiered SmackDown as a weekly series beginning after SummerSlam in August 1999, having initially premiered as a pilot from that April to capitalise on the growing pro wrestling craze. While SmackDown was a major score for the surging WWF, an already-burnt out Russo was much less enthused. He knew that the task of coming up with ideas to fill out two weekly broadcasts was going to be physically exhausting.

Russo also realised that in his capacity as head writer for two shows, crafting the storylines for SmackDown was likely going to dilute the quality of the Raw flagship. WCW had watered down their product by heaping B-show Thunder into their work-week a year and a half earlier, so there was a recent precedent in place.

Russo was also unhappy about money. When he first became the editor of WWF Magazine, his annual salary was $60,000, which rose to $350,00 per year after he became one of the top writers for WWE TV. Russo also received occasional bonuses from the company.

With SmackDown added to the schedule, Russo believed he deserved to be paid more, on account of being an integral part of the WWF's overall turnaround over the previous two years, and being tasked with writing twice as much television as he did before.

That September, Russo met with McMahon for what turned out to be a pivotal sit-down. There, an emotional Russo lamented about the toll that the job had taken on his family, and asked McMahon for a stronger lifeline. A lighter schedule wasn't possible, so Russo asked McMahon to make it worth his while financially. According to Russo, McMahon dispassionately told the writer he made enough money, and that he could just hire a nanny to watch his kids. Following the meeting, Russo knew he would be leaving the company.

Russo told Wrestling Inc. in 2014: "It was a couple of things. I was burnt out and didn't appreciate Vince adding SmackDown without a heads-up or help. Number two, Vince was adding a show that would bring in millions of dollars in revenue and our salary did not go up one cent. I went into Vince's office at that point and I was starting to breakdown because he was milking me dry. Part of what I was telling Vince is that I'm away from home, my kids are young, I wasn't seeing my kids at all, and I was neglecting my wife.

"I'll never forget Vince looked me in the eyes and said 'I don't know what the problem is. I pay you enough money to hire a nanny to take care of your kids.' When he said that to me as a man, father, and husband, that was the end of the line. I was slapped across the face with how little he cared about me as a human and how little he cared about my family to even come up with the idea of hiring a nanny for my kids.

"At that point in time, there was no turning back for me. I was done and because of that I would never take back or rethink anything I've done or have any regrets. That was the lowest thing Vince could have said and it was the end."

While Russo was an integral part of WWF creative, he had been working for the company without a contract which meant he would be able to leave the company at any time. WCW was in a severe state of flux at the time following Eric Bischoff’s ousting from power within the promotion just weeks earlier.

On October 1, one day before WWF Rebellion, Russo reached out to former colleague JJ Dillon, who had been back with WCW for several years. The following morning, Russo flew to Atlanta and met with several WCW officials, including Dillon and showrunner Bill Busch. At the secret meeting, Russo sold Busch on his value as creative shot-caller, with the towering success of Attitude Era WWF backing up his claims.

That Sunday, WCW offered Russo a staggering package of a three-year deal with near-total creative control and what Guy Evans' Nitro called a "generous base salary...augmented by bonuses for achieving targets related to Nielsen ratings and pay-per-view buyrates."

Though the deal was for three years, Russo bargained it down to two years, a concession owed to his still-lingering creative burnout. In his mind, Russo wanted to work for two more years and then get out of the business.

Additionally, Russo wouldn't be coming alone. He advocated for WCW to hire Ferrara as well, and he too received a two-year deal to jump ship. It was reportedly Ferrara that insisted on a "pay-or-play" stipulation within the contracts which meant that both men would be paid for the full amount of their deals, even if they weren't around for the duration of said deals.

By late Sunday evening, the contracts were finalised. McMahon and company returned to the United States to find that their top two TV writers had crossed over to the competition, without giving any formal notice. The WWF website acknowledged Russo's exit in a terse statement, before moving on.

Russo recalled telling McMahon about jumping ship:

"What sucks is the minute I got on the plane to go to WCW, I knew it was over. There's no way I could have met with WCW and not said anything to Vince. That's me. I met with WCW on a Saturday and they wanted to keep me until Sunday. Keep in mind, Raw was Monday so on Sunday I actually signed a contract. I had to fly from Atlanta back home and there was a stopover in Philadelphia, so I got into Long Island at about 2 AM. In the layover from Philadelphia, I had to call Vince on the phone and tell him. I had no choice, Raw was the next day.

"Back then, if you had one conversation with WCW, there was no two weeks notice. I had to explain to Vince what happened and at the beginning he thought I was ribbing him. I told him this was no joke and I start work with them tomorrow. At that time, Vince was floored. There was a point where he tried to make it ugly by sending every lawyer after me and WCW. I said, 'Vince we don't have a contract. We never had a contract. You never cared enough to give me a contract. You're going to send a lawyer based on what?' I eventually said I'm not going to let this get ugly, that's not how I want this to go. I shut it down and told Vince I wasn't going down that road with him. I made a decision that was best for me and my family.

"Finally, I got Vince at the end of the conversation to say I hope our paths would cross again and I said, so do I. Rewind back a week and he should have thought twice about those comments about my family and me. There was nothing, is nothing, and never will be anything more important to me than family. When he made light of that in his office, to me, right then and there it was over."

Of course, Russo and Ferrara weren't the saviours some expected them to be. Bringing "Crash TV" to World Championship Wrestling didn't immediately right the ship - in fact, it exposed just how empty the concept can be when you don't have dynamic performers like Steve Austin and The Rock to carry sometimes-ludicrous concepts. Also, a lack of filters around and above Russo meant that more unrefined ideas - if not outright bad ideas - made the airwaves.

WCW's metamorphosis into Attitude-lite failed to restore the promotion's dimming wattage, while the WWF motored its way into a banner 2000.

WCW in 2000 was nothing short of a disaster. After a few ineffectual months in office, Russo refused a demotion into a creative committee and walked out that January. He came back in April as part of a joint partnership with an also-returning Eric Bischoff which started with some promise, but also went south before long.

Russo was then involved in the fiasco at Bash at the Beach. By the middle of autumn, Russo (who briefly reigned as WCW World Heavyweight Champion), was done with the company altogether. Months later, the WWF bought WCW's most desirable assets for themselves.

Russo bounced around the business from there, writing for TNA for several protracted spells, while ranting on podcasts about the state of the business. His last association with anything resembling a major organisation came with TNA in 2014, where he was last employed as a consultant.

Many individuals jumped ship during the course of the Monday Night Wars. While most of them were in-ring talents, one of the more interesting defections was that of a writer whose name is heavily synonymous with the rise of the Attitude Era.

To whatever degree Vince Russo is responsible for the WWF's late-1990s turnaround can be argued, but what isn't debated is how big the story of his leaving for WCW was at the time, as it looked for all the world like WCW had gotten one over on their thriving competitor. Not so much, it turned out.

Nonetheless, the WWF depature of Vince Russo provides an interesting glimpse at the demands of a pro wrestling TV writer, and how they can face the same career crossroads as the wrestlers they write about.